In the world of global trade, few tools stir as much debate as tariffs. Framed as shields for domestic industries or weapons in economic stand-offs, tariffs can reshape markets, tilt competitive landscapes, and leave lasting marks on entire value chains. So what is tariff?

A tariff is essentially a tax that a government charges on imported goods, added on top of the product’s price when it enters the country. Usually calculated as a percentage of the item’s value, this extra cost makes foreign products more expensive.

Governments impose tariffs for three main reasons – to raise revenue, to shield domestic industries from external competition, and sometimes to pressure other governments during trade negotiations. By making imported goods pricier, tariffs discourage their consumption, steer buyers toward locally-made alternatives, and ultimately support domestic producers by reducing pressure from foreign competitors.

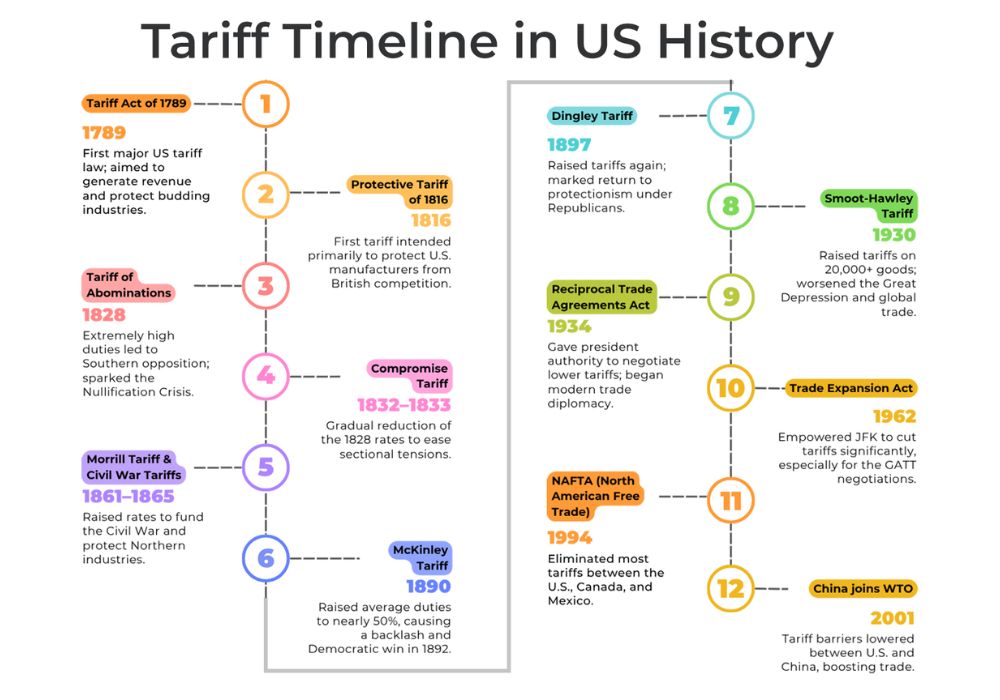

The history of tariffs can be dated back to 1789, introduced by Alexander Hamilton, America’s first Secretary of the Treasury. A visionary for American manufacturing, he saw protective tariffs as essential to weaning the country off its reliance on British and European imports. For Hamilton, tariffs were not merely fiscal tools but strategic levers to cultivate a robust, independent industrial base. This was followed by subsequent tariffs in the coming years till 2025.

Tariff enters the aluminium industry

When talking about tariffs, Donald Trump’s contribution is by far one of the most talked about.

When Donald Trump announced tariffs on aluminium imports in 2018 under Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act, it sent a seismic wave through global trade corridors. Intended to revive domestic manufacturing and protect national security, the decision marked the beginning of a complex and often controversial policy that would continue to echo across global markets until 2025. By the time Trump returned to office and doubled down on the tariffs in his second term, the aluminium industry both in the US and abroad had undergone a dramatic transformation.

In March 2018, the Trump administration imposed a 10 per cent tariff on aluminium imports, targeting countries like China, Russia, and even long-standing allies such as Canada and the EU. The rationale was straightforward – the US aluminium industry had been under pressure for decades, with smelters shutting down and domestic production unable to compete with low-cost imports. The tariffs were framed as a lifeline for American metal producers and a move toward self-reliance in critical manufacturing sectors.

Initially, the tariffs did boost optimism among US-based aluminium producers. Companies like Century Aluminum and Alcoa welcomed the decision, ramping up production and reinvesting in domestic operations. However, this optimism was short-lived. While the upstream segment of the aluminium value chain benefitted, downstream manufacturers especially those relying on imported semi-fabricated products faced rising costs. From beverage can producers to auto manufacturers, industries that used aluminium as a raw material found themselves absorbing higher prices, leading to inflationary pressures and supply chain disruptions.

By 2020, data showed that US aluminium output had improved slightly, but not enough to significantly reduce reliance on imports. Moreover, the added costs were passed on to consumers, with everyday products like cars, washing machines, and canned beverages seeing price hikes. While the tariffs were expected to restore balance, the reality was more nuanced America still needed foreign aluminium, especially higher-quality grades not produced domestically.

The global reaction was equally intense. Canada, the largest supplier of aluminium to the US responded with retaliatory tariffs, sparking trade tensions even among allies. European and Asian exporters scrambled to reroute supply or absorb losses, while some foreign producers began shifting their operations to avoid the duties. This led to accusations of “trans-shipment”, countries allegedly importing aluminium from China, processing it minimally, and re-exporting it to the US under different origins. These practices prompted further investigations and, in some cases, more restrictions.

Fast forward to 2025 – Trump back in office

Fast forward to 2025, with Trump back in office, the tariff strategy didn’t just return it escalated. In June 2025, the administration doubled aluminium tariffs from 10 per cent to 20 per cent and expanded their scope, including stricter origin rules. The new policies targeted not just raw aluminium but also semi-finished goods and components used in sectors like electric vehicles, renewable energy, and construction. While this pleased protectionist factions and select US producers, the broader industry braced for deeper shocks.

The aluminium tariff war had unintended consequences for innovation and sustainability as well. Aluminium, being lightweight and fully recyclable, is crucial to the clean energy transition. EV manufacturers, solar panel assemblers, and green construction firms voiced concern that higher import costs would delay projects, increase carbon footprints, and ultimately hurt the very goals the US aimed to achieve through climate commitments.

Despite mounting evidence that the tariffs were causing as much harm as benefit, the administration remained committed. Federal customs revenue hit record highs, but the downstream industries that make up the majority of the aluminium consumption ecosystem bore the brunt. Some manufacturers delayed expansion, others relocated operations overseas, and many passed on costs to end consumers.

In hindsight, Trump’s aluminium tariff policy between 2018 and 2025 was a double-edged sword

Tariffs initially offered short-term relief to US primary aluminium producers, helping to boost production and stabilize prices in the early months following their 2018 implementation. However, by mid-2019, their positive effects had begun to dissipate, undermined by declining domestic demand and broader market weaknesses. The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic further exposed the limitations of the tariff policy, raising serious questions about its long-term effectiveness.

While the tariffs succeeded in curbing imports and briefly increasing domestic production, these gains proved unsustainable. Today, the US aluminium industry is grappling with a deeper crisis. With only four smelters still in operation, the sector faces mounting challenges, including soaring energy costs and intense competition from global producers especially China. Despite the Trump administration’s 25 per cent tariff on steel and aluminium imports, the US primary aluminium industry continues its steady decline.

The New Madrid smelter, once touted as a poster child for Trump’s 2018 aluminium tariffs, briefly sprang back to life after bankruptcy revived by the 10 per cent duties on aluminium imports. But that revival was short-lived. Tariffs alone couldn’t keep the operation afloat. A similar fate met Alcoa’s Intalco smelter in Washington, where ambitious restart plans collapsed by 2023, resulting in permanent closure. Even Century Aluminum’s flagship Hawesville plant, which once produced 250,000 tonnes of primary aluminium annually, now sits idle.

With aluminium critical to both national security and the clean energy transition, the time has come for a strategic reset to secure the future of the aluminium sector.

We want to hear from you! Be a part of AL Circle’s upcoming e-Magazine, “American ALuminium Industry: The Path Forward.”Share your thoughts, bold ideas, and expert opinions as we explore what’s next for aluminium in the United States.