Two sister metals that are everywhere in our lives: Aluminium and magnesium

Magnesium is the third most common metal and as a structural material after steel and aluminium. It is also the metallic material with the lowest density used in industry.

Magnesium and its alloys are characterised by advantages such as lightweight, high specific strength, good damping and machinability, which make them promising structural materials.

Traditionally used in transportation, aluminium alloying, steel desulphurisation and magnesium alloys diecasting.

Image used for representational purpose

| Magnesium | Aluminium | |

| Melting point (◦C) | 650 | 660 |

| Boiling point (◦C) | 1091 | 2470 |

| Vapour pressure (Pa) at melting temperature | 408 | 2.42×10-6 |

| Density of liquid phase (g/cm3) | 1.584 | 2.375 |

Table 1: Comparison of the main data with aluminium and magnesium

Magnesium and aluminium are two lightweight structural metals and each has its own advantages in industrial applications. Aluminium gives natural resistance against corrosion through its oxide layer, while magnesium has electromagnetic shielding capabilities and vibration dampening. Also, magnesium is the lightest structural metal, 33% lighter than aluminium.

Magnesium

Magnesium was discovered about the same time as aluminium. Sir Humphrey Davy, the British chemist, first extracted aluminium in 1807 and identified magnesium in 1808. Davy discovered many metals and other processes; however, he always said his greatest discovery was Michael Faraday. Faraday produced magnesium metal by electrolysis of fused anhydrous magnesium chloride in 1833. Commercial production of magnesium by electrolysis is credited to Robert Bunsen, the German scientist, who made a small laboratory cell for the electrolysis of fused magnesium chloride in 1852.

Commercial electrolytic magnesium began in Germany in 1886, using a modification of Bunsen’s cell. The Aluminium und Magnesium Frabik, Hemelingen (Germany) designed and built a plant for the dehydration and electrolysis of molten carnallite.

The history of magnesium, from a curiosity metal to an industrial material, was greatly affected by wars. While the Germans were developing magnesium production and uses in the early 1900s, they were also spurred along by the need for magnesium in the military.

In the mid-1990s in China, a variation of the silicothermic process developed by Dr Lloyd M. Pidgeon in 1940-41 began to be used to meet almost 90% of the country’s magnesium production and remains the most common production process.

Magnesium production in China was approximately 810 thousand tonnes in 2023 and China’s production of primary magnesium accounted for approximately 85% of the global magnesium supply.

Magnesium production paths

- Hydrometallurgical processes: Hydrochloric acid leaching to produce magnesium chloride solution, followed by thermal hydrolysis or electrolysis to produce magnesium. The electrolytic process, or hydrometallurgical process, is mainly used to produce magnesium from carnallite, salt brines and seawater. In this process, magnesium chloride (MgCl2) is extracted, dried, melted and reduced in a direct current electrolytic cell to produce magnesium.

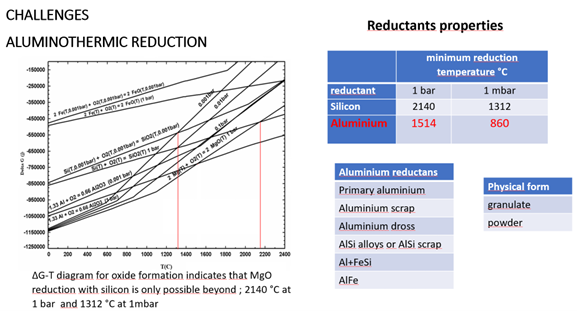

- Thermal reduction processes: Mainly dolomite calcination, thermal reduction and recovery of condensed magnesium vapour. The thermal reduction method utilises a reductant such as silicon or aluminium at an elevated temperature and low pressure to extract magnesium from calcined dolomite. Currently, the majority of magnesium is produced using the Pidgeon Process, which is one of the thermal reduction methods (silicothermic reduction). Reduced carbon emissions of thermal reduction can be realised through the use of renewable energy, as well as utilising aluminothermic processes, where the ferrosilicon reductant is replaced with aluminium.

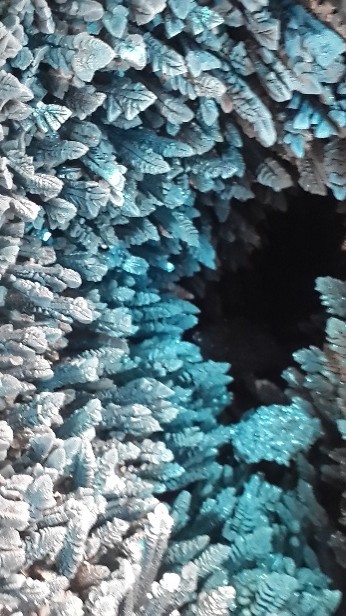

Figures 1 and 2: Pidgeon retort and pellets inside

Figures 3: Crown magnesium

Aluminium-Magnesium Alloys

Magnesium is an essential element in aluminium alloys due to its ability to increase strength, enhance corrosion resistance and improve workability. In the context of concerns about the sustainable future, the demand for aluminium-magnesium alloys will continue to increase, especially in transportation sectors where lightweight is required.

From aerospace to electric bicycles and beyond, aluminium-magnesium alloys represent the future of sustainable and high-performance manufacturing.

Also read: Recovery of alloying elements from scrap along with aluminium recycling

The relationship between magnesium content and alloy properties can be complex. The simple explanation is that in aluminium-magnesium alloys, magnesium atoms replace some of the aluminium atoms in the crystal lattice. This substitution helps in the formation of a solid solution, which strengthens the alloy through solid-solution strengthening.

However, the presence of magnesium also affects ductility, which is the ability of the material to deform without fracturing. Typically, increasing magnesium content can lead to higher strength but lower ductility. Balancing these two properties depends on the precise control of magnesium levels during the casting and rolling of aluminium ingots.

It’s used generally in two major series:

- 5xxx series: These alloys exhibit a high strength-to-weight ratio with excellent corrosion resistance and a wide range of applications

- 6xxx series: Combines magnesium and silicon for heat treatment.

Moreover, magnesium improves the corrosion resistance of aluminium, particularly in saltwater environments, making these alloys essential for marine applications.

Conclusion

There are two aspects of sustainability in metallurgy and material science:

- Sustainability of metallurgical processes and downstream processes

- Sustainability enabled through new materials/alloys for dematerialisation

Figure 4: Aluminothermic reduction

From a metallurgical perspective, newly developed primary magnesium production methods can significantly increase both process and energy efficiency and, consequently, decrease carbon emissions. Aluminothermic vertical retort technology, developed as an alternative to Pidgeon technology, which relies on silicothermic reduction with a horizontal retort and which is also based on metallothermic reduction, can be exemplified as new metallurgical applications that directly address sustainability concerns.

Over the past decade, magnesium and its alloys have begun to be used in a variety of new applications, including biomedical devices, energy storage/battery products, computers, consumer electronics and communications, while also becoming increasingly common in areas requiring lightweight materials. The challenges in downstream applications that limited the use of magnesium and its alloys are gradually being overcome.

This aspect expresses the contribution of magnesium and its alloys, as a sustainable metal, to reducing carbon emissions.

Therefore, technological advancements in the design of both new magnesium alloys and new aluminium-magnesium alloys (high-magnesium alloys), along with their subsequent application areas and the resulting increase in the variety of end products, offer a bright future for magnesium.

The person I always think of when writing this article or doing any research related to magnesium is:

Figure 5: Mr Magnesium (Bob Brown, 1931-2024)

I’ve always thought of aluminium as the go-to lightweight metal, but magnesium’s strength-to-weight ratio really opens up new possibilities, especially for the transportation industry. The fact that magnesium’s alloys can be used in diecasting is fascinating, too!